I found Disco’s Revenge on a plane ride this summer. If I had known about it when it was brand new last fall, it might have been a nice rejoinder to Yacht Rock: A DOCKumentary, which attracted so much ROR reader attention around the same time. Instead, the film seemed to go from the festival circuit to the friendly skies without much press coverage outside its native Canada. (Even Variety interviewed the filmmakers, but never reviewed the movie.)

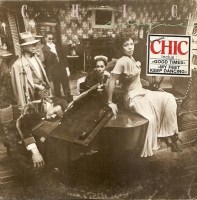

Disco’s Revenge was a perfectly engaging 100 minutes, powered by interviews with Jellybean Benitez and pioneering DJ Nicky Siano, whom I haven’t seen extensively interviewed before, and with Nile Rodgers, who, happily, has been very present over the last five years. Rodgers was on previously reviewed podcasts from Friends of ROR Michael Friedman and Steve Greenberg, whose Speed of Sound podcast included a definitive four-part look at the genre.

What Disco’s Revenge doesn’t include is much about disco’s actual revenge. It begins with Steve Dahl’s July 1979 Disco Demolition, which would have been the logical starting point, and instead flashes back to a lot of the territory covered elsewhere, including Rodgers’s now-ubiquitous story about the Studio 54 doorman who inspired “Le Freak.”

When the bandwagon-jumping that diluted disco in 1979 is discussed, the Ethel Merman Disco Album is trotted out, but Rod Stewart, Cher, and Wings get a pass. So do Pink Floyd, Loverboy, J. Geils, Billy Squier, Queen, and all the other acts whose disco records somehow got positioned as rock’s revenge at the time. In retrospect, that hypocrisy rankles as much as any overt bigotry in the “Disco Sucks” movement.

Disco’s resurgence is limited in the film to two developments over the last 45 years: the Chicago house-music scene of the late ’80s (relatively obscure to mainstream U.S. audiences except in its own echoes) and Rodgers’s own 2013 comeback with Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky.” The movie’s title comes from a reference to Chicago House as “disco’s revenge,” but, really, disco’s revenge has happened many times since 1979, at least musically.

The first resurgence happened within a few years. Even though both Benitez and Rodgers are represented here, there’s nothing about the mid-’80s dance resurgence that their colleague Madonna helped make official. Although the filmmakers are Canadian, there’s also nothing about Montreal or its contribution to disco, or any of the other markets (Miami, California, the UK) where disco remained dominant, even during the early ’80s.

If you were chronicling disco’s revenge, you might want to include:

- 1983 – Shannon’s “Let the Music Play” becomes one of the first inarguably R&B disco records to cross over during CHR’s resurgence. One of its earliest pop stations is WLS Chicago, which had become “rock radio with jingles” for a few years. After two previous singles that had few places to go at radio, Madonna’s “Holiday” breaks through as well.

- 1986 – Led by KPWR (Power 106) Los Angeles and multiple musical movements, dance-focused Top 40 stations quickly become the most compelling thing on the dial for the next three years, especially when Mainstream CHR is playing Peter Cetera and Mr. Mister.

- 1987 – Propelled by the rise of WPOW (Power 96) Miami and WQHT (Hot 103.5) New York, Freestyle becomes a movement unto itself for the next 3-4 years and continues on the concert circuit nearly 40 years later. SiriusXM’s app-only Freestyle Dance Channel made a cameo on its Studio 54 channel last weekend, playing the greatest hits of the rhythmic CHR/freestyle era from the Jets to Cover Girls to Rockell.

- 1993-95 – At Top 40’s very lowest point, when it is most eclipsed by Alternative and Hip-Hop radio, the best records that CHR owns are dance/pop from Snap!, Real McCoy, and LaBouche.

- 1996 – The WKTU New York brand returns to New York, propelling not only a dance renaissance, but also the building blocks of Top 40’s explosion the following year. Often those 1993-95 records are used as currents when new CHRs launch. Even in the early ’00s, when dance has been again eclipsed by rock and Hip-Hop, one of CHR’s few defining records is the DJ Sammy & Yanou version of “Heaven.” (Once again, in the UK, dance remains vital.)

- Mid-’00s – A decade earlier, WKTU helped bring a handful of ’70s dance titles back from exile. Now, the Bee Gees, Donna Summer, and KC & the Sunshine Band are making their way into Classic Hits and Mainstream AC libraries. Until AC moves away from the ’70s, disco is a significant part of the recipe.

- 2009 – “Turbopop,” the place where bubblegum and EDM intersect, becomes the core sound in Top 40’s last big moment to date. It ends when some of the dance hits become harsher, but also when some of its own producers lose interest and move on to other sounds. At the end of Top 40’s mass-appeal era comes “Uptown Funk,” saluting all the dance/funk/R&B hits ignored in the early-’80s disco backlash.

- 2020 – “Blinding Lights” may be the year’s most enduring anthem, but Dua Lipa’s retro disco makes her the early ’20s’ most consistent hitmaker. Drawing on the lushest of late ‘70s disco — more “Last Dance” than “Le Freak” — disco will inform hits from Ariana Grande to Lizzo to BTS to Sabrina Carpenter’s breakthrough “Feather.” Even this week, the Jonas Brothers, already having ventured into DNCE, are saluting the Bee Gees on “No Time To Talk.”

I’m aware that this is a very partial timeline, with some of ROR’s biggest fans already poised to debate or offer additions. It’s not hard to see how the makers of Disco’s Revenge didn’t get to much of it, when Greenberg’s Speed of Sound needed four episodes.

One of the reasons that disco has been able to cycle through pop music so many times is because it’s mostly just music now. It’s not related to either the underground culture that spawned it in the early ’70s (which the film does chronicle well) or the corny mass culture that popped up around it. Each time it returns to pop music, it’s by a new generation of artists drawing on 40-plus year of references.

Even in the early ’24 moments before Carpenter’s “Espresso,” I remember writing that neo-disco felt as ubiquitous as its spring ’79 predecessor. Often it recalled the corniest pop disco bandwagon-jumping of that era. Hearing it sure didn’t feel like justice for Sister Sledge. Plus, one of the mid-’80s effects of Power 106 was to siphon disco away from the R&B radio where it had lived during the first half of the decade, which was happy to switch to New Jack Swing, then Hip-Hop-inflected R&B instead.

It’s interesting that disco continued to boom and bust even after current rock stopped being its competitor. If the rivalry of the late ’70s/early ’80s is still playing out anywhere, it’s on Classic Hits radio, where PDs were happier to play Journey and Cutting Crew than any R&B beyond Michael Jackson, Prince, and one Whitney Houston song. Interestingly, that sort of revisionist history is starting to give way as Classic Hits moves into the ’90s and ’00s, where Hip-Hop and R&B are harder to avoid.

So are we in another disco down cycle? Looking at the charts, I sense more that neo-disco has spent itself out, for a while, than that there is a concerted antipathy again. I certainly wonder if Country’s crossover success is a comment on disco, but there have been neo-disco hits in Country (as well as a neo-soul entrant in the new Miranda Lambert/Chris Stapleton duet). Disco still has some footprint at R&B/Hip-Hop, as evidenced this week by Tyler the Creator’s “Ring Ring Ring.” I think of indie pop as our most intriguing sound now, but the Sombr song that dropped last Friday, “12 to 12,” is his neo-disco exercise. For acts that pride themselves on versatility, disco will always be in the toolbox.

Because Disco has had its revenge so many times over, there’s not much for it to prove, even if we don’t have another slew of hits that sound like “Last Dance” (or, really, its imitator, “Come to Me” by France Joli). R&B and Hip-Hop crossovers are the ones that have had a rough road over the last decade, and I feel better about even their limited presence now. The question in our current stagnation is whether anything as new or exciting can emerge again and, if so, will all sorts of contemporary music converge as they did in the ’70s?

This story first appeared on radioinsight.com